From infancy upwards our girls have always appreciated the convenience and p1easure of locomotion. The bassinet and mail-cart for baby are quickly followed by the governess or pony-carriage, the tram, bus or train, to introduce the world from the door of the homestead as the stages of girl-life to womanhood come and go. The cycle and motor are but after-reflections, representing speed rather than comfort, and are more for the impetuous, adventuresome. and travel-loving members of the family group.

The craze for abnormal speed with motor-cars has passed like a hideous nightmare, and to-day paterfamilias and materfamilias have determined to harness this racehorse-carriage for modest motoring purposes. To go flying through the air, here, there and everywhere, is all very enjoyable as a momentary excitement, but the delight of the English lies in peaceful ways and pleasurable methods. From being a millionaire's ridiculous plaything, the auto-mobile will be evolved into the handmaiden of those of moderate incomes.

The question of initial cost, upkeep and the choice of a motor vehicle lies as much in the size of the house and garden gate as the extent of the income. Car-keeping people can be divided into three divisions; those possessing an ordinary single garden gate, pathway, with hall or corridor for storage, those rejoicing in a double garden gate and a dry shed or cycle-house, and the remainder delighting in a carriage-way and coach-house.

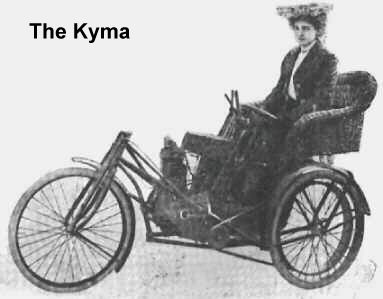

For

the single garden gate villa there is the motor-bicycle with its

detachable trailer or sociable side-carriage, which is a capital

piece of machinery, easy of propulsion, and capable of much hard work

and heavy load in the hands of an expert, provided it is fitted with

a twin-cylinder and about four-horse engine-power. With the double

garden gate there is a greater range of choice. The most dainty

little car, of pretty design, is the "Morette," then there

is the " Kyma", at fifty-nine guineas for one and

sixty-nine guineas for two passengers, the "Tri-car," the

"Century Tandem," etc. All of these require a perfectly dry

shed or cycle-house, and cost from £54 to £125. Cheap cars

abound everywhere, but being 4 feet 6 inches wide, 8 feet 6 inches

long, and 4 feet 6 inches high, they require a carriage-way and gate.

With the larger car there is cleaning difficulty, which is sometimes

insurmountable unless a mechanic is employed, and although the

initial cost is only from £125 to £200, the upkeep is

considerably enhanced when storage and cleaning have to be added to

the expense.

For

the single garden gate villa there is the motor-bicycle with its

detachable trailer or sociable side-carriage, which is a capital

piece of machinery, easy of propulsion, and capable of much hard work

and heavy load in the hands of an expert, provided it is fitted with

a twin-cylinder and about four-horse engine-power. With the double

garden gate there is a greater range of choice. The most dainty

little car, of pretty design, is the "Morette," then there

is the " Kyma", at fifty-nine guineas for one and

sixty-nine guineas for two passengers, the "Tri-car," the

"Century Tandem," etc. All of these require a perfectly dry

shed or cycle-house, and cost from £54 to £125. Cheap cars

abound everywhere, but being 4 feet 6 inches wide, 8 feet 6 inches

long, and 4 feet 6 inches high, they require a carriage-way and gate.

With the larger car there is cleaning difficulty, which is sometimes

insurmountable unless a mechanic is employed, and although the

initial cost is only from £125 to £200, the upkeep is

considerably enhanced when storage and cleaning have to be added to

the expense.

Some of these conveyances, both expensive and cheap are to be seen daily, plying their way along our country highways and town thoroughfares, having been tried, tested and not found wanting, whilst others are still in a purely experimental stage of construction. Such a car, for instance, as the "Morette," while being dainty and beautiful in design and build, and apparently perfectly manageable in the hands of a lady, is still being experimented with, and when perfected will be the car par excellence for modest motorists, seeing that it only costs about £84, travels some twelve to fifteen miles per hour at a cost less than three farthings per mile, including ordinary repairs and renewal, will take all ordinary hills, carries two passengers, is easily handled in case of temporary breakdown, and well within the powers of a girl-driver.

It is interesting to note that Miss Dorothy Levitt drove a car continuously during the eight days' Reliability Trial organised by the Automobile Club this autumn, negotiated stiff ascents, skilfully handled the machinery down formidable descents, and through the crowded thoroughfares of London, Southsea, Margate, Eastbourne, Brighton etc. This achievement is the more praiseworthy seeing that it was accomplished in competition with other cars under very severe test conditions, with no repairs en route in case of breakdown, and with no cleaning throughout the whole period. So it has been proved conclusively that motor-car driving is not beyond the powers of an ordinary English lady who is not gifted with amazonian strength.

The car driven by Miss Levitt was the "Gladiator," of 12 horse-power and cost £540. The term "horse-power" may be confusing to the uninitiated, but when properly understood it is very easy of comprehension. An ordinary horse, or a "hay-motor" as it is sometimes styled, carries its own weight, just as a girl-cyclist does when she mounts her iron-steed, and in propelling her wheel conveys her cycle and herself as she drives. A motor-engine has to be placed in the car. A horse-driven carriage to go at a certain speed and to carry, say, two passengers, counting the driver, requires, according to the style and build of the conveyance, either one, two or four horses, but the motor-carriage demands double or treble horse-power, inasmuch as the motor-machinery is not only very heavy but is dead-weight. So two horse-power is required for an automobile where one horse would be sufficient for a horse-driven carriage. Thus, in speaking of horse-power in motors, it should be remembered that it ought to be halved to compare favourably with a horse-driven vehicle. Hence, two horse-power represents a carriage with one horse of ordinary capacity. But, like everything else, there are horses - and horses. Some are gifted with good staying powers and speed capacity whilst others are noted for "Old Dobbin's ways!" So it is with motors. A motor waggon can be possessed of 20 horse-power, and yet only be capable of travelling some eight to ten miles per hour, seeing that it is built for heavy loads and not for speed purposes; whereas another 20 horse-power car, built on delicate lines like a race-horse, is capable of running 25 miles per hour, and carrying some four to six passengers, inclusive of the driver. There are. then, the race-horse, the ordinary roadster, and the little car of convenience styles of motor carriages, and it is with the latter the chief interest lies.

The charm about this coming horse is that it does not eat its head off! If not wanted, it can be left, perfectly unattended, for days, and even weeks and months, in a dry shed, without any injury or loss of its original powers. This is surely a consideration when the question of cost and upkeep have to be tackled. True, it stops occasionally on the road, and refuses to budge an inch, and most inconveniently sometimes-but so does a horse. It is undeniable that a sensible car will do more for rural England than any other invention. The bicycle is all very well for the active and hearty, but for a family vehicle a dog-cart or pony-carriage is indispensable, and it has been conclusively proved. that if speed he not the sine qua non, the initial cost and upkeep of a modest motor is less than that of a horse.

Of tried and tested cars there are the "Humberette," costing £131 and £147, the "Baby Peugot," £175, the "Oldsmobile," £150, etc., all of five horse-power, and of guaranteed capacity. Any girl or boy can easily drive these little vehicles and they rarely get out of order, but they require cleaning, oiling, and some attention of a mechanical kind, should they become temporarily disabled. Therefore if one pound per week is allowed for upkeep, the initial cost for first year is well under £200. In calculating upkeep some mechanical assistance is included in the £52 per annum estimate. In rural rusticity, if there is a garden adjoining, it is generally the custom to engage the services of a skilled gardener, either for part or whole time. For instance, a doctor purchased a motor-car, and with his wife considered the question of ways and means. They ultimately decided to part with the services of one of their indoor maids, and engage a "motor-man," who would clean and take entire charge of the new vehicle, and spend the remainder of his time in doing odd jobs about the house and garden. In this manner the household gained the invaluable advantages of an ever-ready, speedy carriage, which conveyed the doctor on his rounds visiting his patients, took the wife and family on their various excursions abroad, and fetched visitors from the railway station, to say nothing of innumerable little journeys to the nearest town for shopping purposes, etc. When the yearly accounts were audited, it was discovered that the convenience and advantage of the motor vehicle had in reality saved much personal expense, and at the same time had yielded pleasure and happiness to the members of the household hitherto unenjoyed. The change in the household management, therefore, had proved to be more economical than the reverse. Hence it is advantageous, previous to the purchase of a motor-car, to form a committee of ways and means, in order that the pros and cons of the whole situation may be discussed in all its bearings.

A motor, unlike a horse, is capable of unlimited exercise provided it is kept in good working order, and the cost of mileage is unparalleled. It has been estimated that the average cost of a trip to Portsmouth from London and back, some one hundred and forty-four miles, for petrol and lubricating oil is only five shillings. No horse can do that mileage in one day, and whatever distance he is capable of covering, there is to be added to his expenses the cost of upkeep, which is infinitely greater than that of the horseless vehicle, which only consumes en route, and devours nothing when stabled.

As to reliability, it was proved conclusively during the recent trials that the cheaper cars were really more reliable than the more costly ones. Out of one hundred and four starters for the eight days' contest seventy-five cars of all prices finished, while twenty-nine dropped out for various reasons. Of these, four cars had "non-stop" eight days' journeys, three of which cost under£400, the remaining one costing £975. The same can be said of horses, for the expensive racehorse is delicate, whereas Dobbin is the more suitable for every-day usage.

The coming summer, if only it will be fine, is full of prospects of enjoyment, as motor-car touring will come into favour, and picnics in the country, away from the noise and bustle of town, will take the place of more expensive modes of pleasure-seeking. A motor-car is capable of carrying a great deal, and a day in the country, arranged spontaneously on a fine morning with no premeditated preparation, will be the new way of spending holidays. The sun shines in the heavens, the motor is ready in the coach-house, and a pleasurable outing is secured, without consultation of railway guides, for the world waits at the end of the carriageway beyond the garden gate, ready for exploration.

For modest motoring it is imperative to be able to paddle ones own canoe, i.e.,to study the mechanism of the motor and learn its little ways, even although a mechanic or chauffeur is engaged. These estimable experts always have a keen eye to business, and if anything goes wrong with the machinery, they prefer to send it along to be overhauled rather than have the trouble of seeing to it themselves. But apart from this, the care of an engine is like the care of a house; the care of a dog, cat, or other loved object is best in the hands of its owner. Have a mechanic if possible, by all means, but let him work under your directions, and study the intricacies of your engine yourself. Herein lies the chief interest of motoring. There is no greater fascination than the power over machinery that will obey almost instantaneously your slightest bidding. You touch the levers, the engine starts, and away you go, quick or slow, up hill or down dale, but, ho, presto, you and it suddenly stop. What is wrong? If you know your engine, you will undoubtedly have learned its little weaknesses, will soon discover what is amiss, and again it is doing your will obediently and without any pause in its steady rhythm of beat. There is not a more harmonious sound in the stillness of the night than this steady beating of the engine as the car glides its merry way almost noiselessly along the white roads, lighted by your glowing lamps.

If the car stops, and no matter what you do, refuses to budge an inch, there is an opportunity afforded you to show your inexhaustible patience, forbearance and good temper. This alone is an education in itself! But it will not be for long. After about six months' experiences of various temporary breakdowns, the inexperienced motorist becomes initiated in the motor's little ways, and then come that curious sense of peace and contentment so appreciated by the expert. To show the possible reasons for breakdowns it is interesting to refer to the causes of retirement during the reliability trials. These were troubles connected with the clutch, engine heating, gear, chains, bent axles and connecting-rods, broken wheels, ignition failure, chain sprocket, cooling fan smashed, collision, etc. The moral is, always give individual attention to the engine yourself, and train your ear to detect any sound in its working that points to strained or breaking parts, and this alone will spare the motorist many unpleasant episodes on the road, for a careful inspection of the machinery when the car is stored should betray weak points.

Like the bicycle, the wearing parts of the motor are principally the tyres and chains. But cars have two systems of driving: by means of what is called the "live-axle" in which the rear wheel itself is made to revolve, carrying the wheels with it, or with a chain by which the wheels are driven round. The "Humberette" and "Baby Peugot," for instance, are driven by means of the back axle, while the "Century" has the chain method. "When doctors differ the patient decides." So it is with motors. Various well-known experts are enthusiastic concerning both the chain and axle, and the amateur has the privilege of testing which is the best. There is this to be considered in case of accident : the chain can be handled by the novice more easily than the axle, which demands the services of an expert mechanic. If a chain gets loose, it can be taken off as easily as that of any bicycle, tightened, cleaned and attended to, then put on again; whereas the axle works loose, makes much noise, and is troublesome to repair. Yet cars of good make are fitted with both the axle and chain systems. The pioneer cars used to have belts of leather, but these have been totally discarded, and even a motor bicycle is rarely to be seen nowadays driven by leather, for steel has taken its place.

Then there is the question of side-slip. This, the same as with the bicycle, generally occurs through bad driving along with an abnormally greasy thoroughfare. The remedy is to keep to the middle of the road as far as possible, never to travel on a slanting surface, and to go slowly and cautiously keeping hold of the wheels by means of the brakes. Slow travelling is imperative, as to suddenly put on brake-power to avoid collision generally leads to danger and even disaster, for the car becomes absolutely unmanageable, and sometimes swings round in a circle or turns over.

Modest motoring will introduce to its votaries joys that have hitherto been beyond the reach of the million, as in the early days of automobilism it was only the wealthy who could enjoy this fascinating mode of locomotion, and yet the day has now come when the family of moderate income, can engineer their little car along life's happy ways. Apart from the pleasure of the pastime and the convenience of this system of locomotion, the motor will give to humanity a new possession, and will bring with its use a trained skill hitherto unenjoyed. The care of such delicate machinery and its skilful handling will bring into play unused and dormant talent, for judgement and resourcefulness will be required from the motorist, and our girls will now have an opportunity of showing their skill and prowess in the manipulation of a horse of steel, gifted with powers of speed and locomotion that have to be tried and tested.